09/16/2025

Go tell the Spartans, you who read: We took their orders and here lie dead.

This should’ve been finished weeks ago, when I was still in Greece and everything was going pretty well, till I reached Sparta and checked in to a five star hotel where I was the only guest. That’s where I got sick.

Unaware of what was to come I headed for Nafplio on the Aegean side of the Peloponnese. To get there, I drove across the Taygetus mountains on a highway of spectacular beauty, arriving at my final destination tired and sore. Of course the parking was nowhere near the hotel—I came not to care—but if dragging my luggage through the streets was no fun the hotel was perfect. I checked in, got myself to my room and collapsed. I slept for twenty hours, waking from time to time in a fever, the sheets soaked with sweat. Next day I sort of pulled myself together enough to eat something then slept again. That evening I went to a clinic recommended by the hotel where a doctor, after conducting no tests or taking my temperature—“You have a fever”, he said. “Yes, I know,” I replied—told me that I had vertigo and prescribed some very unpleasant pills. All this time the hotel and clinic staff were wonderfully kind in that Greek way so I didn’t feel entirely alone, but clearly I wasn’t well. Anyway, over the next few days I improved enough to limp my way to a beach so that even if I couldn’t get to see the ruins at Mycenae—the reason I was there—I could at least lie in the sun for a couple of hours.

Getting myself to the Athens airport became my chief concern. Once there I stayed overnight at the airport hotel and flew to Newark the next day. Since arriving home I’ve been able to get to my doctor, undergo tests, and begin treatment. Thanks to antibiotics the UTI went away, came back (not enough antibiotics, unless this was a return of the Lyme I came down with before I left home, or was it something worse?), and was treated again (more antibiotics). If my plan had been to return to Ithaca next month, September, when I’d been promised the island with the colors and fragrance of fall, that rapidly became unrealistic, so I made bookings for April of next year. ‘At your age can you wait that long,’ my doctor, with his usual lack of tact, wanted to know. We shall see; but that’s when I’ll return to the same room in the same hotel at Nafplio, along with Ithaca, Athens, and maybe Olympus: I’ll see what I wasn’t able to see first time. In the middle of all this, bloodwork, physical therapy, etc., I got covid. I’m still positive but feeling only that I might have a slight cold as I wait to be able to reschedule the stuff I had to cancel. And I must say, I’m feeling pretty good; recovered; no longer convalescent. Anyhow, back to Sparta:

According to Plutarch, writing three or four hundred years after the event, in 219 BCE when the Spartan king Cleomenes realized that instead of being an honored guest he was in fact a prisoner at the court of the recently crowned pharaoh Ptolemy IV Philopator, he made a plan to break out of the palace in which he and his friends were being held and in the process liberate Alexandria. When the escape didn’t work as planned, they found themselves without friends or allies facing defeat and dishonor. Instead of surrender—what no true Spartan could contemplate—Cleomenes urged them all to die in a manner that would be worthy of their achievements, so each stabbed himself to death til only Panteus was left. Most daring and fearless of the Spartiates, famously handsome in his youth and Cleomenes’ lover, who now charged him, before stabbing himself, to make sure that each of the others was truly dead, which he did, jabbing each with his dagger, looking for signs of life. When Panteus touched the king on his ankle, he saw his face twitch, so he kissed him and sat beside him till he finally expired when Panteus embraced the corpse, stabbing himself to death over it.

Is this story believable? It’s touching in a gruesome kind of way, a very Spartan kind of heroism and love, but who witnessed it when no one was left alive? Plutarch’s account of the subsequent execution of Cleomenes’ mother and children, and of Panteus’ extraordinary wife who made sure the others were decently covered in death before lying down to compose herself for the executioner’s sword, are pitched to the same heroic scale. Such stories were believed and admired in antiquity and have been ever since, examples in courage, examples we would do well to follow if we dare.

Whoever’s been doing Sparta’s PR over the years has done a bang-up job. An early, but not contemporary apologist, Plutarch wrote that if you were to look at what Athens left behind, its great public buildings, temples, theaters, schools of philosophy, etc, you’d reckon her to be a mighty power indeed; conversely, if you looked at what Sparta left behind in the way of public monuments you’d think her paltry, when in reality it was the other way round. Instead of the inward-looking, paranoid, cautious, isolationist, semi-psychotic death cult, obsessed with personal honor, and riddled with superstition, that I see, it has been widely regarded over the years as an exemplar of courage and selfless devotion to duty. English public schoolboys were subjected over the years to imitations of a Spartan system of education, one that involved a good deal of corporal punishment and no hot water, in the process forgetting that in its later years Sparta was notoriously corrupt, its leaders as eager to take bribes as a Supreme Court judge.

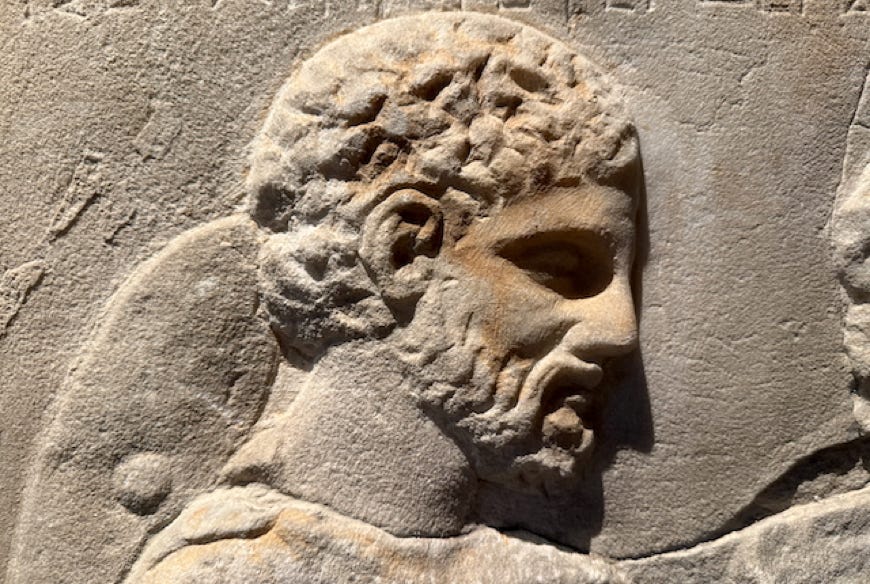

Five wooden villages, a few dance floors—Spartan men were famous for their dancing which might seem odd in a warrior society, but since the dances would all have been based on war moves and gave the men a chance to display themselves it’s maybe not so strange; gymnasiums for the endless naked workouts—a Spartan innovation—and to practice the sometimes lethal wrestling and boxing, plus some small temples dedicated to their own local gods of Fear and Shame, Aidos, close companion to Nemesis, goddess of vengeance, an ancient cult also followed at Athens though without the same toxic intensity, a goddess who recently seems to have come into her own again here in the US.

A Spartan boy, taken from his parents at seven to be raised communally, one who’d been through the grinder and hit all the marks growing up to win the approval of his elders, would be admitted into one of the exclusive barracks to eat, sleep, and live along with his comrades who all thought like him. As Spartiates they were not permitted to do anything but hunt, practice dance moves and work out, maybe dabble in politics and fall in love with each other, to do anything else was ignoble; a Spartiate caught doing any kind of work would be stripped of his citizenship. All this was supported by a system of slavery very like that of the American South, even to the extent of isolating their enslaved population by ethnicity, Messenians in the case of Sparta, the people who lived over the mountains through which I drove, the state next door against which Sparta launched several campaigns till they got their way, compelling a defeated population to grow their food and do their work. As part of a young Spartan’s education, he was given a knife and a cloak and sent out to steal what he needed to survive, killing any Messenians who got in his way for the space of a year; at which point he’d be a true Spartan, a Spartiate, who wasn’t much use for anything except fighting and refusing to listen to reason.

Needing an ATM, I asked at the desk of the horrible five-star hotel in which I seemed to be the only guest where I would find one. Sparta, they told me. You’ll find one in Sparta. Not far. Only four or five kilometers. That the home of Leonidas, birthplace of Helen and Penelope, should be equipped with ATMs gave me a jolt, similar to seeing traffic jams in Thessaloniki on the Maps app; I was expecting ox-carts? What was it I’d been expecting as I planned this trip? Why wouldn’t the modern commercial city of Σπάρτι have ATMs? It’s a busy, good-looking regional hub, of apartment buildings, shops, and businesses.

It was about eight a.m., the town was just getting itself ready for the day, shopkeepers sweeping sidewalks and cleaning windows. And all within a few kilometers of Mystras where I’d been staying which had seemed lost in the countryside—at least as far as Siri was concerned. It had been Sparta I’d wanted to see, the fourth of the city-states of the heroes of the Iliad—Mycenae would be the fifth of the places associated with the Iliad on my itinerary—not the ruins of the Byzantine fortress/religious center/town that climbs a cliff-face in stages, church on church: I guess I can admire Byzantine ruins but they don’t make me gasp in wonder. The travel agent who’d booked me had been adamant however, so there I was, looking for an ATM.

Never back down was their thing. Never surrender. The famous watch cry of Leonidas II at Thermopylae. The obvious question any sensible person might ask is, Why not? A question that was in fact asked by Athenians appalled by such folly, as they watched him prepare to sacrifice himself and three hundred of Sparta’s best-trained and best equipped fighters to prove a point during what was only a rear-guard action intended to provide cover to the allied Greek troops as they fell back in preparation for the larger stand against the Persian invaders that was to come, the battle that would prove decisive. Instead, the obsession with personal honor, with manhood, kept the Spartans locked and loaded because there was no plan B so far as they were concerned. No shade of doubt was allowed, they were prepared to die and in that way achieve a glory that would last forever. Only men with male children had been picked, so their names wouldn’t die out. It’s assumed that their sacrifice inspired the rest of the Greek states to pull together against the invaders, but surely a well-conducted retreat, having delayed Xerxes’ massive army for days, would have done the same? And maybe more, since the Spartan heroes would have been on hand to lend encouragement. Some of the allies also remained in the pass, though Leonidas tried to send them away: not wanting to share the glory? Elians, Thespians, Thebans. “Eat a good breakfast,” he reportedly told the assembled men on the morning of the third day, their last, “You will eat your dinner in Hades.” It’s possible he said something like that, it’s certainly part of the Sparta myth. And perhaps it’s true, or perhaps that’s what he said before every battle. He already knew they’d been betrayed, that a Persian detachment was being shown a path over the mountain that would bring them out behind the Spartan line, that there was no way it was going to end well. So yes, grandstanding aside, such courage is admirable.

Or is grandstanding essential to this kind of public courage? Without a witness to record events, to enshrine last words, what’s the point of making a last stand? The three hundred Spartans prefigure the three hundred Thebans, the Sacred Band, who died at the battle of Chaeronea when Philip of Macedon (Alexander’s dad) defeated the Greek allies to bring their independence to an end. Surveying the battlefield slaughter, as Napoleon liked to do, Philip wanted to know who the men were who’d all died together, each embracing another. The Theban Band, he was told, most fearsome, most famed of Greek warriors, made up of lovers fighting at their beloved’s side, men who refused to be parted in life. ‘Then let them be united in death,’ Philip might have said but probably didn’t. He did, however, have the men buried in one large grave, uniting the pairs so they would never be separated.

I visited Chaeronea, because an important motivator for the trip was my desire to see the places where men had been able to love each other openly, often warriors or athletes, where their loves were celebrated and their lives honored; Thebes and Elis, for example, where men could marry, become ‘yoke partners’ as the Greeks of the time called it since they didn’t have anything like a marriage ceremony. I saw the memorial that Philip had erected—at least that’s one version of how it got there, no catchy epitaph, no go telling anyone because there was no-one left to tell—the lion looking north towards Macedonia. When I asked the very helpful docent about the location of the grave—was it in fact under the lion?—she didn’t know what I was talking about; the Sacred Band that endured for over two hundred years after its founding til it met its end in that place was forgotten. The location and statue were stumbled on, literally, by a group of English friends, using Pausanias as their guide for a tour of Greece in the early 1800s. It took more than a hundred years for the lion to be reassembled in 2902, the money coming from members of the Order of Chaeronea, a forerunner of gay rights groups, a secret society with passwords and initiation rites like the Masons. Living under the oppressive police state that Britain was for its members they had to keep things secret as they began to try to make progress politically. The members funded the restoration and the various pieces of the statue were reassembled with a new plinth and the monument took on its present shape.

The grave itself was discovered and excavated in the late 19th cent when the skeletons of two hundred and fifty-four men were found, laid out in seven rows. There has been a certain amount of controversy about their identity but the consensus is that they are the remains of the Sacred Band. If the story of Philip being moved to tears by their courage seems unlikely—he was notoriously cruel—or that he would have paid for such a memorial, it is countered that he made the city of Thebes pay to bury their dead. Whatever the truth, and whatever version of the story you choose to believe, the Sacred Band was mostly forgotten, apart from those men who looked to them as an example, a different kind of example of heroism and love. They would have been from twenty to thirty years old, the crack infantry brigade, sent in to tackle the most difficult jobs, the first to break the Spartan line that led to their historic defeat at Leuctra. But since they lost their final battle, their sacrifice remained unsung.

Some quotes from Spartan women—Plutarch again—who enjoyed a degree of freedom and personal agency unknown in other city-states, exercising and being educated like boys, with property rights, and the freedom to walk about the city. If they make me think of North Korea, some scholars insist that Sparta not Athens was the true democracy. The attitudes these quotes reveal show how thoroughly the women had assimilated the heroic ideals of their menfolk, husbands, brothers, fathers. Mothers’ day can’t have been much fun.

A woman, as she was handing her son his shield and giving him some encouragement, said: ‘Son, either with this or on this. (Ie. Either victorious or dead)

A woman, when she saw her son approaching, asked how their country was doing. When he said: ‘All the men are dead,’ she picked up a tile, threw it at him and killed him (!!), saying: ‘Then, did they send you to bring us the bad news?’ (Because he’d survived to bring the news making him not a man.)

After hearing that her son was a coward and unworthy of her, Damatria killed him when he made his appearance. This is the epigram about her:

Damatrius who broke the laws was killed by his mother.

She a Spartan lady, he a Spartan youth. (There was no appeal and don’t look for mercy. No surprise that the Spartans were revered by Nazi Germany as well as they are today by some Nazis of our own.)

I stopped off at Thermopylae to take a look around. The big roadside memorial isn’t quite complete but the whole thing is kind of tacky and the exhibit in the mostly empty museum is pretty thin stuff. I may not be a fan but if you’re going to make a memorial it should be better than this. Judging by hats and tee shirts, a few elderly American ex-military were there, guys come to pay their respects. So the memory of Thermopylae still does represent something worth remembering, just as Leonidas planned. The sea is no longer as close as it was, the once-narrow pass has gone, but the mountains remain, more thickly wooded than the rocky, dry desert-place I’d imagined. Unless that’s all changed, too. As things stand it’s difficult to see how the Spartans could have fielded a phalanx, let alone carry out the complex maneuver of making a false retreat then turning on the enemy when they let their guard down to pursue them, a classic Spartan maneuver made second nature through endless drilling.

If they were obsessed with manhood and personal honor, so it seems are we. Some of us, at least. Those of us in the ‘Manosphere’, the constellation of Fox, Rogan, online forums, online ‘news’ sites, etc. Josh Hawley has published a book about it, for god’s sake. I wonder if he mentions running away on January 6? We have Proud Boys with weird initiation rites that involve naming breakfast cereals and their even weirder rules on masturbation. Incels threatening women who won’t date them. And on and on. But we also have sport teams and movies that feature men defending their honor and not backing down: some on horseback, others in space. Seems there’s no getting away from the drive to dominate others who’re just minding their business. Driving onto the Garden State Parkway in New Jersey is to drive into a maelstrom of aggression as drivers refuse to yield to anyone. We all know this stuff, we’ve all seen it. There’s no getting away from the fact that, as a society we are aggressive. So was Sparta. And if that’s a fault it’s also a strength. Or it has been till it’s been so openly exploited lately by bad actors looking to seize control. Even our arts are aggressive. I was working on a musical piece for an Austrian theater so I went to see their production of Dance of the Vampires. It was well staged, lavishly designed and sung in a manner that would have been right at home on Broadway. What wasn’t yet on the same level was the dancing; that was still gentle, graceful, lacking the aggression of American dancers, who come right at you, unstoppable.

I found the ATM, got some money and returned to the five-star hotel. Refusing breakfast I packed and was ready to move on. That I didn’t want to eat eggs distressed the restaurant manager, who presented me with a plate of bacon—I’m vegetarian—and the offer of an omelleta. Instead, I drove up to a lovely open-air dining room where I’d had dinner the evening before—fried potatoes, boiled greens, and grilled cheese—all of it sensationally good, expertly cooked and served with an elegant simplicity. Because my dinner had been so perfect I was heading back up the next morning wanting to eat there once more before I got on the road for Nafplio, my final destination. I ate a breakfast of yogurt drowned in local honey, along with greek coffee—the most delicious I know, I’m already nostalgic, impatient to taste it again—and maybe an orange/honey cake. At that point I’d completely surrendered to the allure of sweetness in the food I was served, the honey, the cake, the salads spiked with bursts of sweetness that surprise the mouth, all the luscious reality of simple fresh food. I’d stopped considering calories and still managed to lose almost thirteen pounds—though the fact that I had been dealing with an injured hip and was about to become spectacularly sick during my final week might have had something to do with it.

It’s that breakfast that remains in memory, that defines for me the brief time I spent close by the city of Menelaus, chief rival of Athens, city of legend and ATMs; the table, the food, the people, the infinite view. I’ve tried to recreate the food here at home but of course I can’t, everything’s off, the yoghurt’s wrong, the honey’s the wrong color, the wrong taste. In the Catskills it tastes flinty somehow, like the mountains, like our rocky soil. Inauthentic, like the Austrian dancers, out of place.

The idea of big strong men dancing in a chorus does seem strange, or did to me, because it was far removed from a corps de ballet or Broadway ensemble. These were war dances and I couldn’t think what that might look like. Then I remembered the Maori haka then, more to the point, the hula of Hawa’ii: men dancing in a way that bonds the group together which was the point of the Spartan dances, to make the men move as one, to get them used to watching out to see what the man next in line was doing, to keep a check on each other, to keep each other alive.