08/28/2023

When the final curtain falls, or the lights go dark, it’s over.

The play is done; the actors take their calls, leave the stage and scramble to change out of costume. All that’s left for the audience is a confused and fading memory. Confused because that’s what the theater does best, create conditions that allow us to fool ourselves into believing that what we know to be false is real, at its most persuasive when it’s telling us what we already know. It’s not best suited to argument or discussion. It’s a place for fine phrases and gesture, for the vivid flash of emotion, for smiling deception.

The audience is in the lobby, putting on coats, blinking in the light, perhaps swapping impressions of what they’ve seen; individuals again, the people they were before they took their seats. They’re outside on the street, raising their collars against the wind and thinking of home.

In the old days, the curtain was late enough for us to have dinner before, then after the show we might go someplace convivial for supper and drinks. But that was when we lived in Manhattan, before we moved away; it didn’t so much matter if we got home late. The theater was more social; in the season we might have gone every week to see what was new, tickets were cheaper, it was all more spur-of-the-moment. It gave us something to talk about, a way to define ourselves. There would often be two intermissions. The eleven o’clock number happened at eleven. Nowadays that’s when stagehands and orchestra go on overtime, so the curtain needs to be down if the show hopes to recoup.

Before turning in we might glance at the Playbill, read some of the bios, think of a line that stuck; the way that actress came through a door; that man’s face in Act Two as he learned the truth. Years later, considering the stack of Playbills accumulated in our playgoing years, we might wonder what the hell to do with them. They’re of no value to anyone. Their only value to us is to jog our memory, if we’re lucky. Remind us that once we were in this place and we did that thing. And so because they retain a certain glamor by association, a reminder of how we were, we’re reluctant to throw them out. Who knows? Some day they might come in handy. Maybe the grandkids will take an interest? (They won’t) So instead of trashing them, along with those other equivocal relics we’re holding on to ‘in case’, we put them in the attic.

Albert Martin and Miss Wolvern will be joined in holy matrimony 1/3/1882

Albert Martin and Miss Wolvern married 1882

Orpah Martin sixteen May 29 1882

(In another, more legible hand) Finished cleaning house May 2nd 1886

I’d lived here for years before I noticed those words scrawled faintly in pencil on the underside of the stairs. You need a flashlight to see them as you go down to the cellar, something I do as seldom as possible. There’s another later, more legible addition in marker, Gene Whiting 1996. It was from Gene that I found out about the names when he wrote to ask if they were still there, addressing his letter to ‘The people in the last house on the road’. He didn’t know much about the names but his aunt Eleanor did, the granddaughter of Tecumseh Sherman Lennox, postmaster, who bought the house and land from the Martins in 1910. She made a lecture about it with slides and pictures that I think she used to give at local libraries and churches. At some point this was recorded on a DVD. Thanks to a filmmaker neighbor I have a copy.

Before we moved in, I spent time clearing out stuff left behind by the previous owner, Gene’s grandfather, son-in-law of TS, as Mr Lennox was known. Emptying out the back porch that’s now the dining room, the few things that I thought worth keeping—like the painted tin ceiling light fixtures from the 1920s when electricity replaced gas—I put upstairs in the attic.

I’m fortunate to have an attic. Everyone should have an attic. Living in city apartments, closets take on that role. If there aren’t any closets we make do with a drawer, or a suitcase, a box. Any place we can put those things—keepsakes, souvenirs, old tax receipts—we no longer need but that we’re not quite ready to trash. Things that have meaning enough to make you hesitate about living entirely without them. Until the time comes when that option no longer exists.

An attic needn’t be physical. It can be a place between imagination and memory to store unfinished projects we’re reluctant to let go; trips we intend to make, places we’ll visit, friends we’ll see again, family we’ve lost touch with, childhood wrongs to put right, old loves that linger. It’s hard to let go of ancient address books, or the contacts on our phone who no longer answer: do we delete their names or is that hurtful? Who does it hurt? Them or us? So much lumber gets piled up in the attics of our imagination, waiting to nag us when we wake late at night and can’t get back to sleep.

Overlooked treasures only lurk in other people’s attics, we know well enough there’s no lost Leonardo in ours.

When I was first alone, I took down shelves I’d built for the stereo we no longer played. If we didn’t play our records, having them around represented the possibility of music, remnants of how we used to live. I put all that stuff in the attic, along with the giant speakers we’d brought from London. Dead media is hard to give away. After I repaired the wall and it was a freshly painted blank, my plan was to hang something new to the house, something bold and bright.

My sister-in-law’s late husband, the artist Frank Fristachi, had made a large work I really admired; when he was alive I’d offered to buy it. Though he’d appreciated my enthusiasm, Frank was leery of letting it go. When I suggested some alternatives, he was also less than enthusiastic about losing hold of them.

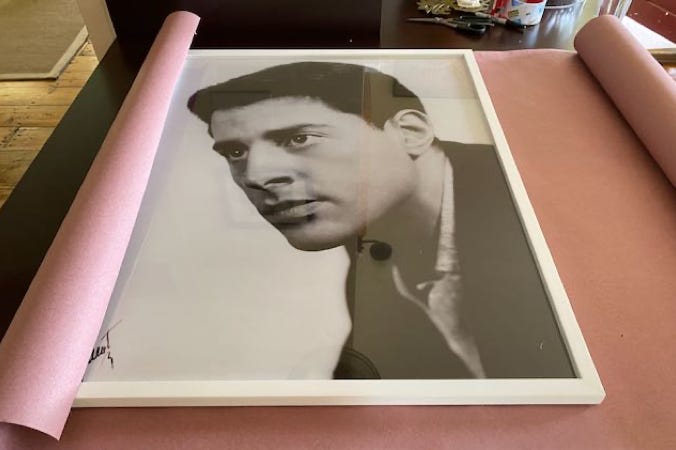

So instead I turned the blank wall into a kind of scrapbook: a diploma for painting I’d won at the age of eight; shots of me in my first West End show; ditto Broadway; a giant portrait of Vivian that I’d had made for his memorial, blown up from a headshot taken when he was about twenty-two and an actor, before he’d started directing; some stills from older plays; posters and announcements of recent work; Vivian and I in early days on holiday in France; my mother as a girl with her mother in Scotland. The jumble it made was a tangible life-line to the past when I needed it, when I would get inexplicably lost in known places, or drive off the road into ditches, when I put locks on the windows and installed a burglar alarm. All the panicked reactions to being alone that followed Vivian’s death, till they began to recede and I felt more at ease.

Sadly, Frank died in a hospital, isolated in the middle of the worst of the Covid lockdown. Recently, his studio and house have begun to be dismantled. Not wanting all of his work to go into storage, to have some pieces up on a wall where they could be seen, I was finally able to bring that big work of his home, along with some smaller pieces. But before putting it up on the wall I’d initially planned for it I needed to dismantle my scrapbook, take it all down, wrap everything individually in Red Robin paper, and lug all those scraps of my life upstairs to the attic.

I used to love saying goodbye! When I was acting, at the end of a run I loved when it was over, getting in a car and driving away: Goodbye…! Good luck…! Thanks for everything…! See you around…! Keep in touch…!!!

There’s a lightness to saying goodbye, a buoyancy to walking out of a place with no knowledge you’ll ever be back (though a hope that maybe they liked you enough to hire you again: (the actor’s curse) In the course of a job, through rehearsals and performances you get to know your cast-mates pretty well; in a way that’s intense, without being lasting or deep. Not that it’s superficial, it’s not, it’s a particular way of relating to strangers with whom you’re suddenly intimate; a professional intimacy that lasts as long as the run. Probably you don’t have much in common beyond the work; when that’s over—despite protestations—there’s no real pull to ever see them socially. You might bump into them in Joe Allen, or at a casting call, or you might even be cast together in another show when, assuming you didn’t end up actively hating each other—it happens—you’ll slip back into your already established intimacy.

It’s not like real life, nor should it be. Confusing the two can only lead to trouble. A showmance is over before you board the plane home. Offstage, intimacy takes time to develop and isn’t contingent on casting decisions.

Despite the brutal lack of security I treasure the theater’s impermanence, as well as its tradition. It’s always been an arena of apprenticeships: you learn by seeing and doing. With luck you’re challenged, you work hard, drink too much bad coffee, and learn lines. Just like actors in, for the sake of a wild stretch though not really, Shakespeare’s company. How did they learn their lines? Pretty much as I recently did, memorizing the text to my solo play Nine Day Wonder which brings alive Shakespeare’s first clown, Will Kempe. Line by line you keep going over it—I use a number ten envelope to screen the text, drawing it down the page as I progress—and slowly you commit it to memory, losing objectivity with each line learned, puzzling out the same problems and pleasures as those Early Moderns, still trying to get the same laughs.

I’m a believer in the holy power of comedy. I write comedies, I’m at my best acting in comedies. I love to act farces. There is nothing so exhilarating. No power quite like bringing an audience to heel. As a young actor I was dismal playing those pro forma juveniles of Shakespeare: Silvius, Sebastian. I got a hint of what I could do playing Charley in Charley’s Aunt before we left the UK, and then playing Brian in the magically, lyrically ridiculous No Sex Please, We’re British, a play that took me completely by surprise when, on the first night in Corning, New York (summer stock: 1978), the audience simply wouldn’t stop laughing. Something similar happened at the first Broadway preview for my play Souvenir when, during Act One, I was almost afraid the laughter would tear the play apart. Almost.

In the States for some reason we like to pretend that we don’t have a cultural history. As far as the theater is concerned we go back in a direct line to the Greeks. And not in a fancy way, but in the way of people trying to pretend that they’re doing real things, acting out a story to make it real for a group of others gathered to watch them, the audience which becomes complicit by believing in the masquerade.

Almost my favorite story about actors and acting concerns Hegelochus, the actor who created the role of Orestes at the Athens Dionysia of 408 BCE. Perhaps the earliest of the very few actors from the ancient world whose name we know because he screwed up so badly. Instead of saying ‘after the storm I see again a calm sea,’ he said (according to Wikipedia) ‘the final word with a rising-falling tone instead of a simple rising tone’, and instead of ‘calm sea’ it came out as ‘weasels’. After the storm I see again weasels, is how I choose to read it.

There is a: nothing about this story that I don’t identify with completely and b: nothing that isn’t hilarious. I have been Hegelochus. We all have in one way or another. The poor man was mocked mercilessly, allegedly retired from the stage, and it seems that Euripides had to get out of town for a while to let the furor die down. I know if I’d been on that stage I would have been helpless with laughter and probably crying. It seems that the audience enjoyed it, too. I can see them hurrying to tell friends who weren’t there, later telling their children, and their children’s children, laughing again at the actor who said weasels.

If Euripides didn’t take it well you can’t really blame him. I know how it is when actors, saying your lines, start talking nonsense. I’ve done the same myself. I remember one matinée in Norfolk, Virginia, playing a long, two-handed expository scene in a farce I love by Feydeau. Rehearsals had been rushed, the part was long, and at that performance I came to a complete stop, could think of nothing to say or do, and had to exit stage left to ask the stage manager running the show from the wings, ‘What the hell do I say?’ As Hegelochus sat backstage, inconsolable in his dressing-room, his mask in his lap, trying to decide if it was too late to begin that career in plumbing that his father had advised, I’m sure his Clytemnestra said to him what my scene-partner, with a perfectly straight face, said to me, ‘No one noticed’.

So you see, tradition.

Coming across the names on the stairs, knowing that what I did in 1999 as I junked the old stuff left behind to get the house ready for us to move in together, and then in 2019 when I did much the same to remake it to be where I would by myself, was what those unknown people did a hundred years before, gave me a similar sense of continuity. I wondered about the newlyweds: how did their life together turn out? And Orpah, what happened to her? Was she still here when the house was sold?

When they were here the house was half the size it is now, there were no neighbors, the hill above was bare of trees, stone walls had been built (by them? by others? who? when?) to contain their cows, there was no reservoir filling the valley, no blacktopped roads, no electricity or running water. When we moved in, no one had used the upstairs rooms in years. If it wasn’t abandoned it was certainly neglected; in what had been bedrooms, covering bare floorboards, I remember patterned squares of old linoleum imitating area rugs, a fashion I’d never seen before. I tried rolling them but they were too fragile. Before walls were pulled down and the old gas lines removed, I set aside a few things to save: a wooden shipping box that I converted to a TV stand; a homemade holder for paper clips and pens that I have on my desk; a wooden chair painted a chipped and battered blue.

Was that something that had been brought here by Orpah’s parents and left behind? Or, like the stone walls, had they inherited it from whoever was here before them? As the house gradually emptied of people, Mr Lennox and his wife gone, then his daughter, their children moving away till only his son-in-law was left, now in his eighties, living in a couple of rooms downstairs, the chair was forgotten when the house was sold.

Stripping the paint off the old fireplace surround and a couple of doors, I thought of the chair and cleaned it up, thinking that some day it might come in handy.

Some day it did. Though now I slightly regret I stripped off the paint. No reason the past has to be perfect. There should always room for weasels.