08/01/2023

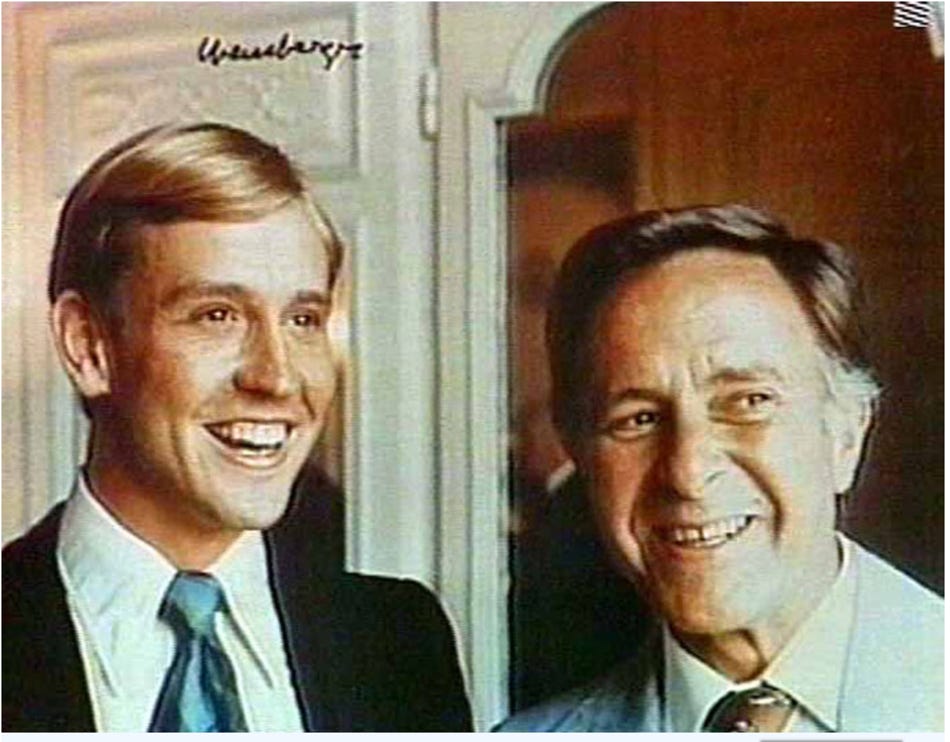

Geoffrey Burridge and Alec McCowen

Likely she’d have denied it but I remember—if I can trust myself—Saturday evenings, like it was an event, my mother would sit down with the dog and a box of Black Magic chocolates to watch the telly. She spent a lot of Saturday evenings alone. My father was a jazz musician and if he wasn’t officially playing a gig he was often someplace sitting in.

One of the shows she’d watch was This Is Your Life, in black and white—they didn’t have color till years later after we’d come to live in the States—watching with the dog while the host, suave and genial Eamonn Andrews in those days, stuck a microphone in some poor sod’s face and said “THIS is your Life.”

I wonder if part of the appeal of the show was the hope that someone would say “Oh no, it’s not,” or, “Let me out!” like the star footballer Danny Blanchflower. When a producer grabbed his jacket to try to stop him, saying “Think of all those people waiting for you!” Blanchflower snapped, “You invited them, not me,” and was out the door. Others threatened to bolt, but none were as successful, perhaps gripped by the very English fear of ‘letting the side down’ or, after their first impulse to flee, being unwilling to take such a drastic public action, held in place by the responsibility owed to family they didn’t talk to or friends they hadn’t seen in years. Once the trap was sprung and the victim had mastered the shock, they were hurried to the studio—I’m imagining limos with black glass driving very fast through darkened streets—to be sat down in a chair while Eamonn opened the Big Red Book and, with a solemn jollity, got down to brass tacks as voices from the past challenged the panicked ‘guest’ to remember that time when.

It happened to a friend of ours. The last time I was in London I brought him to a dinner-party a friend was giving where everyone made a big fuss of him and got him a little bit drunk. Alec was well into his eighties and didn’t go out a great deal; whether from choice or from the inevitable falling-off that comes with age, I don’t know. As an actor he’d spent an unusually long time at the top of his career, always unconventional in a slightly mad way, his respectable veneer masking a seeming out-of-balance derangement put to good use by Hitchcock in Frenzy. When I was twelve or thirteen, I’d seen him play the Fool in Peter Brook’s celebrated production of King Lear for the RSC. I was about to make my stage debut as Cordelia in a school production so my mother took me, thinking perhaps that it would be encouraging for me to see the play being acted by professionals. Diana Rigg, pre The Avengers, pre Bond, was the king’s youngest daughter. Some years later, when I was twenty and first met Alec, he was pleased that I remembered him mischievously popping up from under upturned tables and benches left behind after Paul Scofield as the king, in a fit of pique at being told that his retinue of fifty was no longer welcome—I tend to think Goneril has a point—overthrew all the furniture and stormed off, raging about ingratitude. There was Alec, derisive, sharp, mocking his boss’s eldest daughter even though the time when he could safely get away with it was past.

I didn’t see his celebrated performance in Hadrian VII, either in London or New York, but I did see him in Christopher Hampton’s The Philanthropist, and in John Dexter’s superb production of The Misanthrope at the National Theatre with Diana Rigg as Célimene, both of which productions went on to successful Broadway runs. He also created the role of the psychiatrist in the not-so-superb Equus, also at the National but when that was being brought to New York, Alec bowed out. His first time on Broadway was in ’51, as part of the company performing the Lawrence Olivier/Vivien Leigh double-bill of Anthony and Cleopatra (Shakespeare) and Caesar and Cleopatra (Shaw). In ’57, as Barnaby in the original London cast of The Matchmaker, Tyrone Guthrie wanted to bring him over—Ruth Gordon was Dolly Levi—but American Equity would not give permission and the part went to Robert Morse. He did come to Broadway with After the Rain, directed by Vivian, and with both of his solo plays, in ’78 and ‘81 with his wildly successful The Gospel According to St Mark and in ’84 with Kipling. His last working trip, forty years after his first, was in ’92 with Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me at the Globe when, coincidentally, I was next door at the Shubert with Crazy for You. Alec said he could sometimes hear our band through the walls.

After such a long and distinguished theatre career, and with many TV productions and films as well (the radio operator in the good Titanic film A Night to Remember; opposite Maggie Smith in Travels With My Aunt), his perhaps inevitable encounter with the Big Red Book came in ’89 when he was appearing in Exclusive, a play at the Strand Theatre, London. Though we’d been living in New York for over a decade, Vivian had gone over for what was supposed to be the pre-West End try-out of a new musical and, after finishing a tour of Me and My Girl, I went to visit. So we were at the first night. The curtain was delayed by a bomb threat phoned in by the IRA; we were all detained outside on the street till the police could search the theatre. Much was made of the event next morning in the press, overshadowing the largely derisive reviews of the silly, old-fashioned thriller centered on a corrupt, hard-charging editor of an imaginary newspaper, bewilderingly played by the fastidiously intelligent Paul Scofield. The political notoriety and commercial success of the playwright, Jeffrey Archer, had initially made it seem likely the play would run a year or two. It didn’t, but it was during its run, after I’d returned home and Vivian was packing to leave, that Alec got ambushed by This Is Your Life during a curtain call. He didn’t walk out: what he did was I think more remarkable. Let me backtrack.

I met Vivian in ’69 when I was in an off-Broadway play with an old friend of his. Over drinks after the show, when I talked about how much I needed to get out of the States he said there could be a job for me in London, a small part in a play about Oscar Wilde. When the production fell through he wrote to let me know, but to call him anyway if and when I got to London. After I arrived I let a few months went by, got in touch, went to visit, and pretty soon we got together. He and Alec had known each other for some time and had been very much involved in each other’s lives since they’d appeared together in the London production of The Caine Mutiny Court Martial. As Vivian began to make his transition from actor to director he’d coached Alec, continuing as he began to teach acting at LAMBDA, and then when he began his directing career. By the time I encountered Vivian in London, any romantic involvement between them was over though their friendship remained. He’d been away playing Hamlet at the Nottingham Playhouse, where he met the young man he would come to passionately love and protect, Geoffrey Burridge. The four of us saw a lot of each other, Alec lived near, he and Geoff would often come for Sunday lunch, when Vivian would roast a shoulder of lamb with potatoes. All very domestic and safe; our lives lived behind closed doors.

In ‘77 Vivian and I left London, sailing to the States with our two red mini wire-haired dachshunds on the Mikhail Lermontov, the Soviet Union’s idea of a luxury ocean liner, as sinister as it was absurd. We’d been in New York for almost ten years when Alec let us know that Geoff was very sick, was in fact dying from HIV-AIDS. That they’d kept this a secret wasn’t surprising given the level of hysteria surrounding such a diagnosis at that time, and realistically or not, Geoff wanted to at least keep open the possibility of working for as long as he could. And then he was dead, at the age of thirty-eight. Neither of us could get there for the funeral—I was working and Vivian didn’t fly—but that was okay; before he died, Geoff had picked out the music he’d wanted to be played, and a lot of people were there, he’d been an easy man to like, with his big open laugh and handsome, blond eagerness. Alec didn’t like to talk of that time, how it was for him, or of Geoff’s condition before his death.

Three years later Michael Alred, came out onto the stage of the Strand and stuck a mic in Alec’s face.

After a difficult phone call with Vivian, Alec wrote:

‘I don’t think I have ever felt so empty or sick at heart as I did when I was driven home, alone, after the programme. I felt as if I had been raped. I felt as if I had been captured by the conformists and made in their image. I knew I had been used by Jeffrey Archer and the management to get publicity for Exclusive. And I realized that you and my sister had been conned into cooperating.

‘Yes, I have been angry with you. But that is because you are my closest and best friend… I realize you were placed in a hideous position. But what would you feel if I helped set up a tribute to you without mention of Steve?’

Through our long time together—forty-eight years at the time of his death in 2018—because of the work we did Vivian and I would often be apart, sometimes for fairly long stretches of time. When we were apart, as people used to do, we wrote letters and sent voice tapes to keep in touch. Apart from one series I deliberately kept from 1978 when he was directing Jessica Tandy in a play at Stratford, Ontario, the tapes have gone. Either we recorded over them or they got lost; even the ones I kept are now too fragile to play. The letters we saved; me putting his in various boxes, him keeping mine in brown manilla envelopes, everyday records of nothing much, where we’d been, what we’d been doing, what we were thinking. Perhaps a year after Vivian’s death in 2018, as I was busy remaking the house, turning it from where we had lived into where where I would live, I opened the boxes of letters he’d sent to me—along with birthday cards, Christmas cards when we were apart, first night messages, cablegrams, notes left behind when he went away for work—combining them with my letters to him I sorted the pile into decades, then years, months, days, sliding each message into its own plastic sleeve, assembling them all in ten, fat, three-ring binders. Letters that he’d received from others, including those from Alec, I made into a separate binder. And it was as I was putting this together that I came across a couple of browning newspaper pages.

‘This Is Your Life Star In Gay Shock’, was the front page headline in The Sun. ‘This Is My Gay Life’, was the Mirror, with a sub-heading that pulled no punches, ‘Amazing TV tribute to star Alec’s dead lover’. Alec wrote:

I wish I knew better what went on when it was being set up. I only know there was a bland little programme with a lot of dear old ladies and no mention of you, and no mention of Geoff. …I wish you had warned me, and asked my advice seriously—and then trusted that I would look sufficiently surprised when the time came… I asked them not to put it out because I thought it was a phony cover-up.

Asked them not to put it out—because whose life is it? And if it’s going to be represented, who has the final say? I’m assuming that Thames TV, the producing company, needed his permission to broadcast what was for them a cheap and popular revenue generator. ‘a silly little piece of fireside fun,’ he called it. The Mirror reported in its breathless tabloid manner:

An astonishing public tribute to actor Alec McCowen’s gay lover who died from AIDS… … Bachelor McCowen was upset that nothing was said about his close companion Geoffrey Burridge who fell victim to AIDS two years ago. Now the top actor, who courageously refuses to keep his lover secret is to get his wish… A favorite of the royals, (McCowen) was awarded the CBE in 1986.

’86. The year of Geoff’s death. His apparent ‘closeness’ with the royals was also stressed by the Sun, as if he’d deceived them or worse, as if they’d known but kept it hidden.

‘A top Actor tried to halt a This Is Your Life tribute to him because it did NOT reveal that he was gay or that his lover died of AIDS… For years McCowen lived with TV star Geoff Burridge, 35, who died of AIDS two years ago. But host Aspel made no mention of it when presenting him with the famous red book at last week’s studio recording. Afterwards, angry McCowen—a favourite of the Royal Family—protested that the show was ‘a sham and an insult’ and demanded that it be scrapped. But TV bosses managed to save the show by agreeing to ‘insert’ a short tribute to the actor’s lover at the end of the programme’.

From Alec’s letter to Vivian

‘I said I understood their embarrassment, but the programme was a travesty. I was thinking chiefly of Geoff—but also of the present day atmosphere which is tending to be anti-gay, and less than sympathetic to AIDS… What I regret is my lack of knowledge; that you were shabbily treated; that Geoff was ignored; and that his mother and some of his friends were not invited even to be there.’

In ‘89 the AIDS panic was very real, Princess Di had only taken off her gloves to shake patients’ hands at the London Middlesex Hospital’s AIDS ward in ‘87, HIV had been isolated as the cause of AIDS in ’83, the first case to be recorded in the UK was as recent as ’81, discrimination and demonizing were rampant, and it was against this backdrop that Alec demanded not only that his relationship with Geoff be recognized, but also that his cause of death be named. For the record, they didn’t live together, Alec kept a room for him in his flat that he kept untouched after Geoff’s death, and he wasn’t thirty-five.

‘We never dwell on the sexual side of anyone’s life,’ the producers responded, ‘And thought we were being discreet.’ I’m sure that’s true, conversations were had, assumptions were made. For the time those assumptions were pretty standard; ‘sexual side’, not anything suggesting an emotional bond; ‘lover’ not partner or some other, more meaningful, word. According to the Sun, when the show had featured ‘homosexuals in the past, like Russel Harty (1981, a talk-show host) and (long, long-running TV soap) Coronation Street actor Roy Barraclough (1987)… out of consideration no mention had been made of their gay lifestyle’. If now they sound more than a little indignant it was because Alec’s reaction, his demand, was out of the ordinary, insisting that Geoff, and their relationship, be treated with respect instead of relegated to some shameful back street where they could practice their gay lifestyle, an alleyway down by the gas-works where nice people don’t go.

‘…I have become a tiny hero, and have admiring mail from sad gay men, middle-aged lady fans, two vicars and Ian McKellen and Tony Sher. When I told my mother that Geoffrey had died of AIDS she just said: “Oh that poor boy!”’

Alec downplaying the response to his actions is typical of him; how he expresses it—sad gay men, middle-aged lady fans—is a distancing tactic typical of the time, as typical as the producers of This Is Your Life leaving out what they assumed could only reflect badly on Alec, that favorite of royals, maybe even reflect badly on them, who knows? By leaving out what they regarded as shameful they were in their way trying to protect him. Such heavy-handed censoring seems like a tacit recognition of the intrusive nature of the show itself. But by leaving out Vivian and, more importantly Geoff, they also left out what was unconventional and most alive about Alec, what made him so interesting when he acted, the core of who he was.

‘After I am given the Red Book at the end, they will fade to a photo of Geoff and me, and hopefully Michael Aspel will say “This programme would not be complete without remembering Geoffrey Burridge, who shared Alec’s life for seventeen years, and who died of AIDS in 1987 aged 38’.

Which they did. This is the picture.

One small step, one small solution to what some might see as a small problem. Though Alec was left feeling used and useless, in his way he made a breakthrough. It’s by means of small steps that we progress, when so many small steps are made that the balance tips and we stumble forward.

The programme was aired, with the dedication, in December of ’89. Exclusive had closed, so whatever box-office boost might have been hoped for was not going to happen. Alec went out sandwiched between Zsa Zsa Gabor and Barbara Cartland, with a scion of the Ringling Brothers circus included to keep him company.

He died in February of 2017, Vivian in August 2018. Now I’m the sole witness.

Which is why I’m doing this. To try to find out what remains. At the end of the day, when all passion is meant to be past, what keeps me alive, what holds my interest and, more than interest, my enthusiasm. Because among the many fortunate aspects of my life, what makes me most grateful is my enthusiasm which I feel to be not only intact but increased by my new state of being, my new way of living. And of course I bring Alec with me, and Geoff—the dedication to Songbook will include them both—but most of all Vivian, who showed me how to be human, helped me to grow, and gave me my freedom.