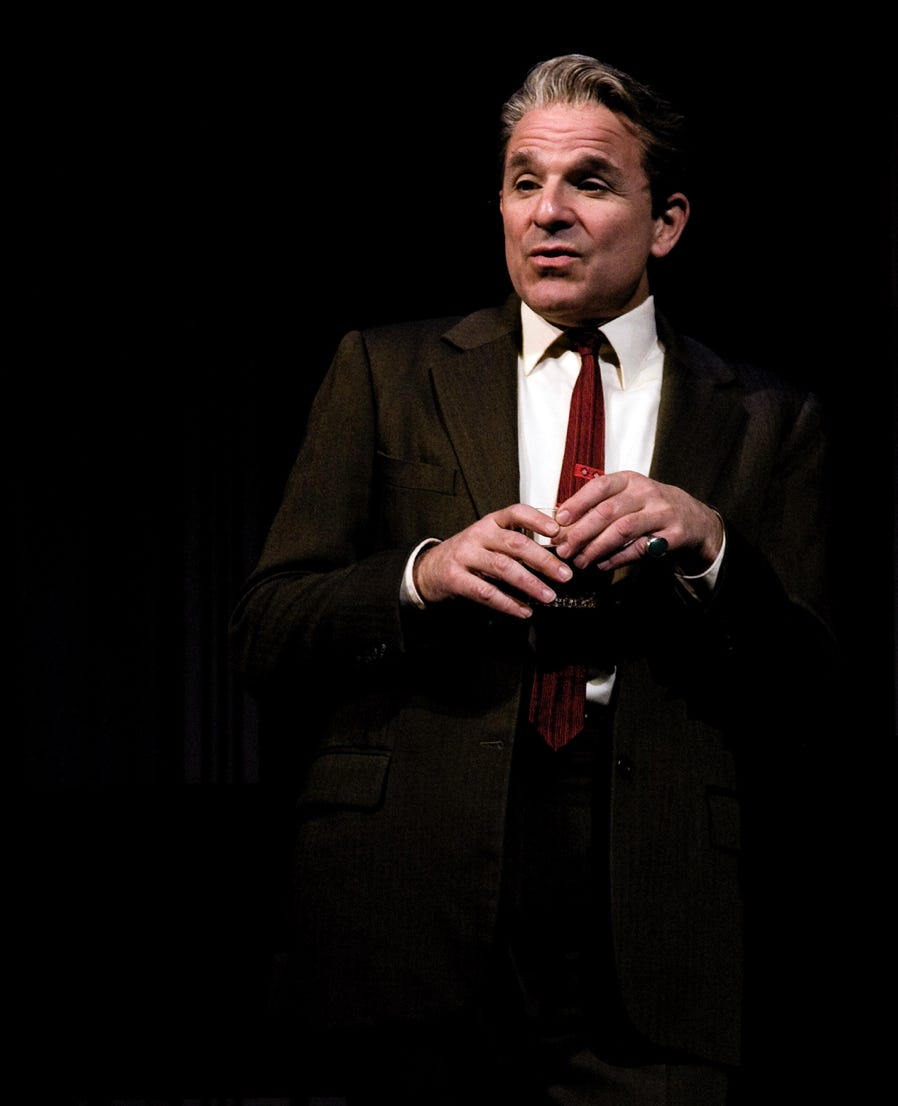

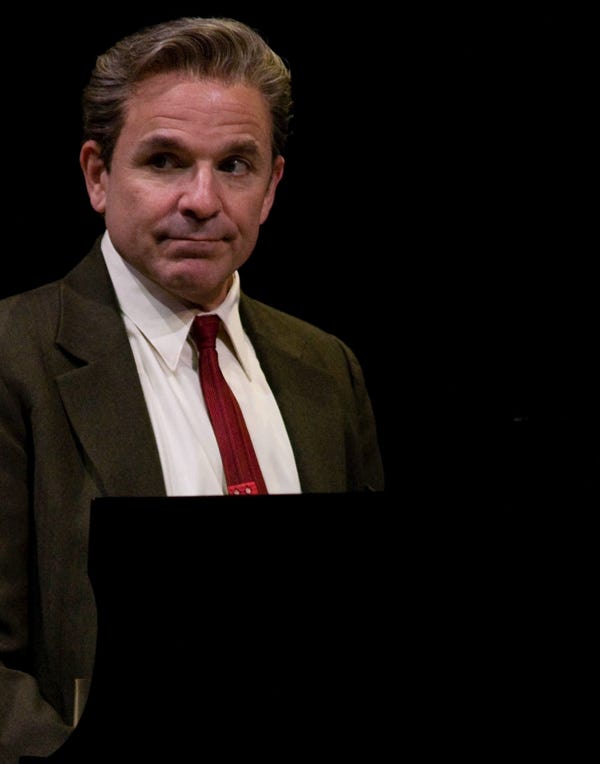

Donald Corren and Judy Kaye at the Lyceum Theater

The Story of the Play

Florence Foster Jenkins, a wealthy society woman active in New York in the 1930s and ‘40s, believed herself to be a great coloratura soprano. In reality she couldn’t sing two consecutive notes in tune.

Undeterred by family criticism she began to give recitals for her large circle of friends in the ballroom of the Ritz Carlton where she lived. Word of the recitals soon spread to the general public and very soon she was packing the ballroom. Despite all the laughter and jeers, the shrieks and howls of derision, she believed the audience was genuinely moved by her singing. A belief that took her all the way to Carnegie Hall for a sold-out concert in 1944, an event that is still talked about.

Over the years, Mrs. Jenkins has become a figure of fun, a camp whose records are played at parties to be laughed at.

Souvenir takes a different approach, seeing Mrs. Jenkins through the eyes of her reluctant accompanist, Cosme McMoon.

When they first meet he regards her as a convenient, if embarrassing, way to pay the rent, worrying what his friends will say. As he comes to know her, however, her unshakable faith in herself and in the music she loves, makes him want to protect her from the laughter he hears when she sings, laughter to which she remains oblivious — till the evening she steps out onto the stage of Carnegie Hall.

When at last she hears the laugher, it is Cosme who rescues her from doubt, helping her to maintain her delusions, staying true to the beautiful music she hears in her head, the music that, in the play’s final moments, the audience hears too.

Donald Corren and Judy Kaye at the Lyceum Theatre

I never intended this play to be what might be called a true account of Mrs Jenkins, or of her accompanist Cosme McMoon, which is why I call it a fantasia.

The real woman was seventy-six when she produced her own concert at Carnegie Hall. The audience went there to laugh at ‘a poor, demented old woman hopping and squawking about the stage’, to paraphrase what was perhaps the only honest review of the event. That seems to me to be unconscionably cruel. When I first heard her infamous record I mostly thought it sad—and very strange. Though it goes without saying that all of us are to a degree blind to our own follies and self-deception, it was the scale of her delusion that seemed, and seems, remarkable.

IMost of of us understand that there’s a difference between how we see ourselves and how the rest of the world sees us. In my play Mrs Jenkins is blind to that understanding, insisting that her own view of herself is the objective truth. Is it the responsibility of her accompanist to stop her making a fool of herself? So far as he’s concerned she’s merely a wealthy woman with no talent and too much time on her hands. But as years pass and his own disappointments pile up he finds that he has come to care for her. Does his responsibility then change?

As Cosme confesses, he never lied to Mrs Jenkins, but he also never told her the truth—which could be even more destructive.

Improbable or not, McMoon’s name was real. Perhaps a Scottish father emigrates to Mexico, marries, has five sons, and gives the fifth and last a name from his homeland—Cosmo. It had been high-class when he jumped a ship to the new world. So his youngest son was Cosmo McMahon. Then Spanish speakers added their own twist. It’s not Cosmé, as some reviewers have gone into print to correct my French—and as it’s mystifyingly recorded at the Carnegie Hall website—though not at the Library of Congress. The songs attributed to him that were sung by Mrs. Jenkins in Carnegie Hall—Like a Bird I am Singing and Serenata Mexicana— were copyrighted in his name. Since you can’t copyright a work under a pseudonym unless you state your real name—Cosme was real.

As a child, he moved from Mexico to San Antonio, Texas, with his mother and four brothers. Then at the age of nineteen he moved to New York and was living in a boarding house on 34th Street. In 1929 he gave a recital in Town Hall—and subsequently met Mrs. Jenkins.

I hadn’t heard the syphilis theory till quite recently: that syphilis caused nerve damage that stopped her from hearing what she was doing. Also why she liked to wear wigs, because she’d gone bald. Certainly none of the people I spoke to who had known her or had attended her recitals brought it up, and it was never mentioned in any of the gossip I read about her. Perhaps someone has seen her medical records and based this theory on what was found there. To my mind it seems to echo Karen Blixen’s accepted biography—young bride (both nineteen) infected by husband on her wedding night; a great love unconsummated for fear of passing the contagion along—in Blixen’s case to Dennis Fynch-Hatton, in Mrs. Jenkins’s to StClair Bayfield. This offers a more sympathetic reading of Mrs Jenkins remaining legally a spinster than my idea, which is that she remained single to keep control of her money, tantalizing McMoon with promises of a legacy that didn’t come about, she died intestate. And the new perception of her that she was a piano prodigy whose career was cut short by her illness which was when she taught herself to sing, seems suspiciously like the biography of Galli-Curci, who was regarded by Mrs Jenkins as a rival.

There is no way to explain away her delusions without diminishing her mad career. I could be wrong about all this—I purposely didn’t see a documentary film about her. It was shown when the play was already running off-Broadway and I didn’t want anything to interfere with my ‘facts’ as we went forward—so perhaps I’m delusional, too.

This website makes use of cookies. Please see our for details.

Deny

OK